Wow. So, it’s been 6 months since my last post.

Chalk the hiatus up to the overwhelming task of writing a dissertation and raising kids. (Generations of female scholars are nodding their heads and playing the world’s tiniest violins for me stumbling at what they’ve done successfully for years and years).

Also – and I share this only because it factors into this post – my son was sick for a while and had to be hospitalized. He’s great now. Just know that PTSD is a real thing and taking time to deal with it is good for everyone.

What drew me out of the fog and spurred this post was a statement that has been haunting me for months. The brilliant scholar and museum historian, Victoria Cain, told me something that shed new light on pretty much everything I’ve been seeing in my work thus far.

My interpretation of what Dr. Cain said, almost as an aside, was that fueling American industry was one of the central goals of late nineteenth/early twentieth century American natural history museums’ efforts to describe the natural world. This industrial agenda undergirded all of the research done in these museums – even the study of people.

In other words, ethnology/anthropology was a project undertaken, at least in part, in service of American and global industrial development. People were seen as key assets and/or impediments to growth of American capitalism, a relationship that museum scientists worked to illuminate. I’m sorry I keep restating the same thing, but its been a jarring insight, and Dr. Cain’s observation snapped a lot of random thoughts and feelings I’ve had into place.

At this point, it’s important to note that ethnology/anthropology were seen at the time as roughly equivalent to botany or zoology; all fields of natural science. I know scientists like to beg off on complicated discussions and some of the darker implications of their work (a damning part of our failure thus far to stop climate change, fwiw), but that can’t be done here.

In 2003, anthropologist Don D. Fowler summed up this fact with brutal efficiency, arguing that in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, “both ethnologists and anthropologists saw themselves as scientists. As such, their task was to generate ‘objective, value-free, scientific knowledge’ about humanity but especially about the commensurability of races. Such knowledge was seen to be essential to resolving ongoing debates about race that swirled through national and international politics and colonial administrations throughout the nineteenth century.”[1] Of course, commerce was and remains central to national and international politics. With this in mind, the idea that anthropology was important to industrial development seems almost obvious.

So…what are we to do with this nugget? First, let’s dispel the myth that there has ever been a time that American science museums have operated without the direct or indirect influence of industry. If you’re concerned about how business leaders shape the public presentation of science, know that it is pretty much an essentialism of American science museums. Our goal should be to understand how the nature of that influence has changed over time. You can argue or be mad about that, but the data are pretty clear. I’m working on a paper that will spell this out in more detail. Also, re-read this paragraph the next time you wonder why your museum isn’t doing more to combat climate change.

Second, we need to place science museums among the many institutions that have promoted the subjugation and exploitation of people for the sake of profit. That’s a crushing sentence to write, but ignoring that point limits our ability as museum professionals to reframe that narrative. And we can’t make any substantive change without acknowledging and working to combat our own sordid history.

Of course, we now need to ask ourselves how museums used artifacts, images, and narratives to promote using bodies for bucks? This is a HUGE question, way bigger than a blog post. To give some sense of the scope of this issue, I’m going to jump to what was probably the most explicit example, Philadelphia’s now defunct Commercial Museum.

Founded in 1894, the Commercial Museum was created to “promote the commerce of America with foreign lands and to disseminate in this country a wider knowledge and appreciation of the customs and conditions of the other nations and peoples.”[2] Historian Steven Conn has done a lot of great work on the Commercial Museum, but in the interest of time I’m pulling straight from original sources; any overlap here with Dr. Conn’s research is accidental.[3] And you should go read his stuff. It’s really good.

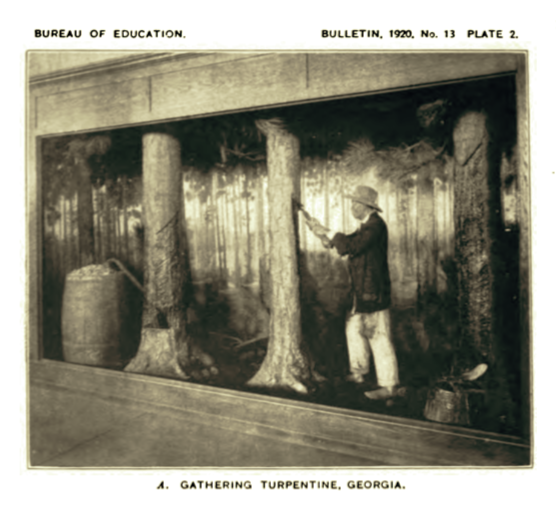

One of the major approaches the Commercial Museum’s leaders used to spur industrial development was to summarize natural resources by region, including dioramas that highlighted how people have harnessed and utilized those resources. Often, native people were presented, essentially, as resources themselves.

For anyone familiar with the history of African peoples in America, the image below is like many you’ve already seen. The context here adds new complexities. This diorama of a woman picking cotton, here labeled causally as “mammy,” was said to draw visitors in, arresting their attention as it were, to learn more about cotton production. It is not intended to show the story of a person in bondage (albeit likely to sharecropping and not slavery). This isn’t an exhibit of displacement and oppression. This display is part of the story of how America got rich and will continue to create wealth. The viewer is to see this woman in that context.[4]

Now, take this image and use it as a lens to look at the history of anthropology exhibits. Sure, this cotton exhibit is an extreme example, and without having done research on anthropology exhibits in museums more explicitly designed as institutions of science, it’s hard to imagine they were this direct in their messaging. I can imagine someone has already done good work in this regard. The answers are out there to be learned, regardless.

Images and exhibits alone can’t tell us how visitors were taught to think about these dioramas on visits to the Commercial Museum. My research focuses on the history of education programs, because I believe strongly that experiences like these were powerful in shaping what school-based and public visitors took from their time in the museum:

I can tell you that from my research, education programs in natural history museums, which were used to enrich, direct, and supplement the ideas associated with exhibits, often referenced or were couched in the industrial applications of what visitors were seeing. For example, at the American Museum of Natural History in 1904, an experiemental school tour program was based around “using the exhibits of the Museum to illustrate the beginnings of human invention and industry.”[5].

Educational programs – including tours, lectures, laboratories, image and object loans, as well as text and slides for teachers to deliver their own presentations in their classrooms, were a major project for the Commercial Museum (see images below from Toothaker 1920). What conversations were being had in classrooms and among student teachers? What did the museum’s lecturers and educationa materials tell students and teachers to think about the people in other countries? About themselves?

I think it’s reasonable to presume (though we’d need some more evidence) that generations of students were taught to see people around the world as sources of, or complications to, earning income for those in economic or political power. Slavery may have ended by the time the Commerical Museum opened, but the ideals that made it possible hadn’t and still haven’t. If anything, there has been a frightening new premium placed on getting as much as possible from people with the least.

This approach of counting bodies as a commercial resource is subtly central to our deeply flawed approaches to increasing diversity in S.T.E.M. (or S.T.E.A.M., or whatever arbitrary acronym is getting the most funding these days). Essentially, many argue that more diversity in the sciences will lead to better science. Women, people of color, and people of varying physical abilities, it is thought, embody different perspectives that can enrich the ideas and innovations possible through research and development. It’s really rooted in Cold War concerns about the scientific workforce, and somebody looked a chart of representation and saw women, brown people, and differently abled people as “market inefficiencies.”

If we were really serious, we’d couch our work in the idea that diversity in S.T.E.M. is needed to ensure equitable access to careers that have been the literal and figurative engines of American commerce. Whole chunks of our society are being systematically excluded from careers that hold financial promise, social significance, and public prestige (well, ok. that last point is suspect these days.), and we all suffer as a result. THIS idea would be a more powerful call for making the science more inclusive. The two arguments aren’t mutually exclusive, of course. Still, is there any wonder that established scientists aren’t fully bought into the idea that the people who they don’t want around are going produce better science than they can make on their own? But, alas, we don’t know much else besides body for bucks.

At the risk of making a crazy leap, I’ve come to think of the modern medical industrial complex as a troubling new extension of this idea that people’s very bodies are sources of income. For various reasons, I’ve spent lots of time in hospitals over the course of my son’s four years, including a week and half in a pediatric intensive care unit earlier this spring. Hospitals always seem to be under construction and expanding. The amount of money flowing through these places is staggering. I’ve also noticed what seems to be rapid growth in the private medical service industry, with dialysis centers, rehab facilities, and diagnostic labs popping up in shopping malls and random corners like modern day liquor stores. In short, treating our fragile bodies and managing the debt we accrue for the privilege have been fueling industrial growth on a startling scale.

Ultimately, the idea that bodies are a source of income requires diminishing the value of human life. People aren’t individuals; they are profit margins. Companies are scrambling to cut salaries and benefits leaving workers less stable and less supported than they have been in generations. Political movements are spurred by fears of immigration; that these new people will take good jobs and comit crimes, because the best jobs usually go to criminals (that started as a joke but it is kinda real). Prisons generate wealth from the slave-like labor of inmates. Heck, even in the sports world players are referred to as “assets,” and “pieces.” It’s everywhere.

Returing to science museums, you might rightly counter by saying they have become spaces where individuals – and how they learn – are deeply valued. As a result, we can push back on these deeply troubling legacy narratives that our institutions helped to create. As educators, we try to enrich and enlighten, but ultimately visitor learning is a matter of individuals exercising their to own freedom to build their own value. When we enable them to do so, we create opportunities for the kind learning that liberates.

That said, we must remain vigilant in ensuring that the messages science museums present are progressive and transformative. Free-choice learning in subtly racist, sexist, classicist, anti-LGQBT, etc., environments still reproduces the kinds of ideas that destroy. We have to be the change we seek, but to do so we have to take a long, hard look at who we are. And then, we have to confront what might be the most difficult question of all: If museums are going to truly value people fully and completely, industry isn’t likely to join in. If that happens, where exactly are we going to find the bucks we need to subsist?

[1]. Fowler, Don D. “A Natural History of Man: Reflections on Anthropology. Museums, and Science.” In Curators, Collections, and Contexts : Anthropology at the Field Museum, 1893-2002, edited by Stephen Edward Nash and Gary M. Feinman, 1525:11–22. Fieldiana. Chicago, Ill. : Field Museum of Natural History, 2003., p. 1. http://archive.org/details/curatorscollecti36fiel.

[2]. The Commercial Museum, Philadelphia : Its History and Development–Collections of the Resources of the World–Educational Work–Assistance to the Business Man. Philadelphia, 1910. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/gri.ark:/13960/t9d54678q.

[3]. I should admit that I haven’t read or looked over my notes on Dr. Conn’s work in about a year. Plus I’m perpetually exausted because I’m raising a toddler so I generally can’t remember much past a few days ago. That said, some of his thoughts could be rattling around in my head and may have seeped out here. Please call me out if you see it. To fact-check me and rake me over the coals later, see Conn, Steven. “An Epistemology for Empire: The Philadelphia Commercial Museum, 1893–1926.” Diplomatic History 22, no. 4 (1998): 533–563. https://doi.org/10.1111/0145-2096.00138., and Conn, Steven. Museums and American Intellectual Life, 1876-1926. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1998.

[4]. Toothaker, Charles R. Educational Work of the Commercial Museum of Philadelphia. Bulletin, 1920, No. 13. Bureau of Education, Department of the Interior., 1921. http://eric.ed.gov.ezproxy.library.wisc.edu/?id=ED543378.

[5]. American Museum of Natural History. “Annual Report, 1914.,” February 1, 1915., p. 52. http://digitallibrary.amnh.org/handle/2246/6228.

Great post, Dave – you always give me so much food for thought. Our museums (and towns and cities and lives) are covered in this subtle (and not-so-subtle) messaging. I’m proud of this project: https://rmsc.org/science-museum/exhibits/item/421-take-it-down-organizing-against-racism . It’s certainly not the end of a conversation but shows that addressing the situation can be more powerful than just removing the perceived source. Museums must become more intentional about outing our own history and that of the communities we serve. We can’t be progressive or transformative until we can admit and address our faults, flawed assumptions, and inaccuracies… and seeing those requires eyes that are all too frequently not at the table.

LikeLike

Thanks for reading! This Take It Down! exhibit looks so interesting. I’m happy that the panel with this racist image has been repurposed to start conversations. I really think the key is to use these images as pathways to learning. Removing them forever can lead to forgetting, which can lead to history repeating itself. Museums are uniquely qualified to facilitate and manage these discussions. I’d love to hear more about how this has been recieved and what you all have learned in the process. Great, great work!

LikeLike